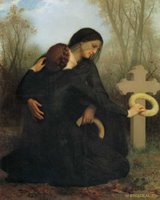

All Saints', All Souls' & Our Prayers.

he past is not dead,” wrote William Faulkner, “it is not even past.” Similarly, in the Church, we can say, “Our dead are not past, they are not even dead.” And they are not. This is much of what we mean when Sunday by Sunday we confess our belief in the “communion of saints” and as we pray in the funeral rite’s Eucharist, “For to your faithful people, O Lord, life is changed, not ended; and when our mortal bodies lie in death, there is prepared for us a dwelling place eternal in the heavens.”

he past is not dead,” wrote William Faulkner, “it is not even past.” Similarly, in the Church, we can say, “Our dead are not past, they are not even dead.” And they are not. This is much of what we mean when Sunday by Sunday we confess our belief in the “communion of saints” and as we pray in the funeral rite’s Eucharist, “For to your faithful people, O Lord, life is changed, not ended; and when our mortal bodies lie in death, there is prepared for us a dwelling place eternal in the heavens.” At the beginning of November, we pay particular attention to our Christian dead with two days of commemoration – the Feasts of All Saints on Nov. 1st (or transferred, as our custom is, to the following Sunday) and All Faithful Departed, more traditionally “All Souls’ Day,” on November 2nd. In the Bible’s way of speaking, all the redeemed are “saints;” the Biblical writers make no distinction between those Christians whose lives of “heroic sanctity” are gratefully recognized and remembered throughout the whole Church, and the “faithful departed,” whose sometimes more and sometimes less holy lives are dear to us personally, or who are remembered no more – all these, in New Testament terms (and in the courts of Paradise) are saints, too. But for pastoral purposes, the Church makes a liturgical distinction between these groups. It has become common practice to conflate these two commemorations, but at St. Joseph of Arimathea we maintain this distinction between All Saints’ and All Souls’.

On All Saints’ Sunday we pay homage to and celebrate those giants whom God has raised up among us, to give thanks for their witness and to “consider the outcome of their way of life, and imitate their faith” (Heb. 13.7). On All Souls’, we likewise come together to give thanks, but this is a bittersweet commemoration. Bitter, because we yet mourn the loss of loved ones; sweet, because we know that though departed this life, they are “with Christ, for that is far better” (Phil. 1.23), and await that great Day when all who have died in Christ shall rise again. This, of course, is the pastoral distinction between the two days: Francis of Assisi and a departed loved one may both be saints in the New Testament sense; but while we need to be humbled and strengthened by Francis’ example, we do not mourn his death as we do that of a lost parent or child. To put it starkly, I admire Francis, but I do not miss him.

In both cases, though, we offer prayers for the departed, as we do at each celebration of the Holy Eucharist. Such prayers are a point of some controversy among protestant Christians. As an example, the Westminster Confession of Faith (c. 1643), the basic doctrinal statement of traditional Presbyterians, states in its Larger Catechism that “We are to pray for…all sorts of men living…but not for the dead” (emphasis added). Suffice it to say that the Reformer’s rejection of prayers for the dead was tied largely to the Catholic practice of saying Masses for the dead which were intended to help speed the departed through Purgatory and on to Heaven, a practice which was in medieval times horribly abused, especially in the sale of indulgences. Nonetheless, the Anglican tradition has retained prayers for the dead, choosing not to throw out the baby despite how filthy the bathwater may once have been, and we may justify and embrace the practice without reference to Purgatory, but by reflecting instead on the nature of life (for the saints and faithful departed are not dead) and on love, which “never faileth.”

The life of the “saints in light” is no static state, and this is not to say that they are undergoing some purgation to fit them for the life of heaven. Instead, it is merely to recognize that God is uncreated and infinite, and we are created and finite. For this God has redeemed us, “so that in the coming ages he might show the immeasurable riches of his grace in kindness toward us in Christ Jesus” (Eph. 2.7). So, the life of the faithful departed in the nearer presence of God is always and ever “higher up and further in.” Which is to say, there is, and will always be, growth in the grace and knowledge of our Lord. To be sure, theirs is no longer a struggle against the world, the flesh, and the devil, but is rather the enjoyment of the beatific vision wherein the saints are changed, transformed “from glory to glory” (2 Cor. 3.18; cf. 1 Jn. 3.2). But prayer may aid enjoyment and rest as well as struggle and trial, and why should not our prayers help in this growth? God will do what he determines to do, and needs no help. But God ordains means as well as ends, and he has ordained prayer as a means by which he will accomplish his purposes. Indeed, St. Paul rejoices that God has made us his “fellow workers,” and one way we enter into this privileged status is by our prayers.

It may be objected that the faithful departed have no need of our prayers – their transformation from glory to glory is a “sure thing.” But God is no less sovereign on earth than in heaven, and still he commands us to pray. Every purpose of God is a “sure thing.”

Beyond all this, love itself demands that we remember in our prayers all those “whose rest is won.” We do not cease loving when the beloved dies, and for Christians praying is included in loving. E.B. Pusey said it well: “Unless there were, in the word of God, an absolute prohibition of prayer for the departed, how should we go on praying for those whom we love until they were out of sight, and then cease on the instant, as if ‘out of sight, out of mind’ were a Christian duty?”

Similarly, C.S. Lewis makes an important connection between the necessities of love – prayer, in this case – and honesty with God: “Of course I pray for the dead… At our age the majority of those we love best are dead. What sort of intercourse with God could I have if what I loved best were unmentionable to him?” (Letters to Malcolm, 107). To pray is to open our hearts to God. As Lewis says, it is our intercourse with him. Refusing to pray for the departed is to close a portion – for many of us a very large portion – of our hearts off to God; it is to say that some of our deepest hopes and longings we may not to tell to God, which is dishonest. And silly, because he already knows.

Which brings us finally to the other side of the question: if we may (must!) pray for the faithful departed, may we hope that they pray for us? While it is not given to us to know to what extent the saints are aware of our needs, certainly they are still themselves; they retain their identity. And who am I? Well, any answer that does not include “Ashley’s husband, son of Jim and Elizabeth, brother of Jimmie and Jennifer” would be less than complete. We are incomplete if we are not in relation, not loving: “It is not good that the man should be alone” (Gn. 2.18). It seems to me that to say the saints do not or cannot pray for us is to say one of two things, neither of which rings true: either that they are no longer themselves, their identity erased, or that their communion with God is less perfect than in their earthly lives. Again, E.B Pusey:

That we have for the time no more to do with those who loved us here, and whom we loved, must be false, because it is so contrary to love. It belongs to the Communion of Saints, that they, in the attainment of certain salvation and incapable of a thought other than according to the mind of God and filled with his love, shall pray and long for us, who are still on the stormy sea of this world, our salvation still unsecured; and that we, on our side, should pray for such things as God in his goodness wills to bestow upon them.

A Collect for the Faithful Departed:

Grant, O Lord our God, that the souls of thy servants and handmaidens, the memory of whom I keep with special reverence, and for whom I am bound to pray, and the souls of all my benefactors, relatives, and friends, and all the faithful, may rest in the bosom of thy saints; and hereafter, in the resurrection from the dead, may please thee in the land of the living; +through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.